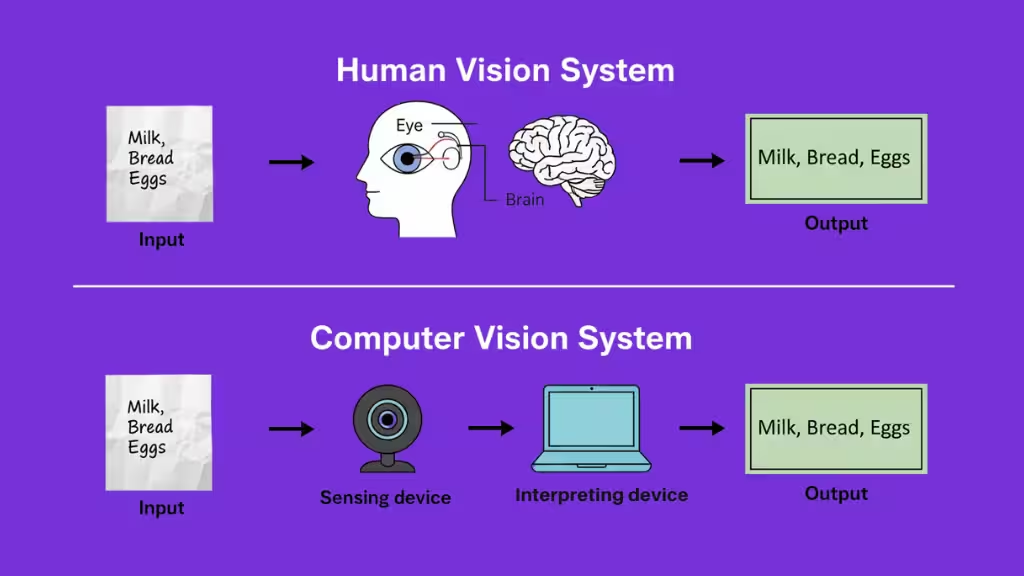

Computer vision is one of the most dynamic and impactful fields within artificial intelligence (AI), revolutionizing how machines perceive and interpret the world. At its core, computer vision enables systems to extract meaningful information from digital images, videos, and other visual inputs, simulating the way human vision works. Whether it’s powering facial recognition on smartphones, enabling autonomous vehicles to detect pedestrians, or assisting medical professionals with image-based diagnostics, computer vision is becoming increasingly central to technological innovation.

What is Computer Vision?

Computer vision is a subfield of artificial intelligence that focuses on enabling computers to interpret and make decisions based on visual data such as images and videos much like the human visual system. Unlike simple image processing, which might involve adjusting brightness or removing noise, computer vision aims to understand and analyze the content of visual inputs in a meaningful way.

At a fundamental level, computer vision systems are designed to answer questions like:

- What objects are present in an image?

- Where are those objects located?

- How are they moving over time?

- What is happening in the scene?

To do this, computer vision combines principles from machine learning, pattern recognition, neural networks, and signal processing. Thanks to advances in deep learning, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), modern computer vision systems can now perform tasks with remarkable accuracy from facial recognition and medical diagnosis to object tracking in autonomous vehicles.

Two Key Technologies of Computer Vision

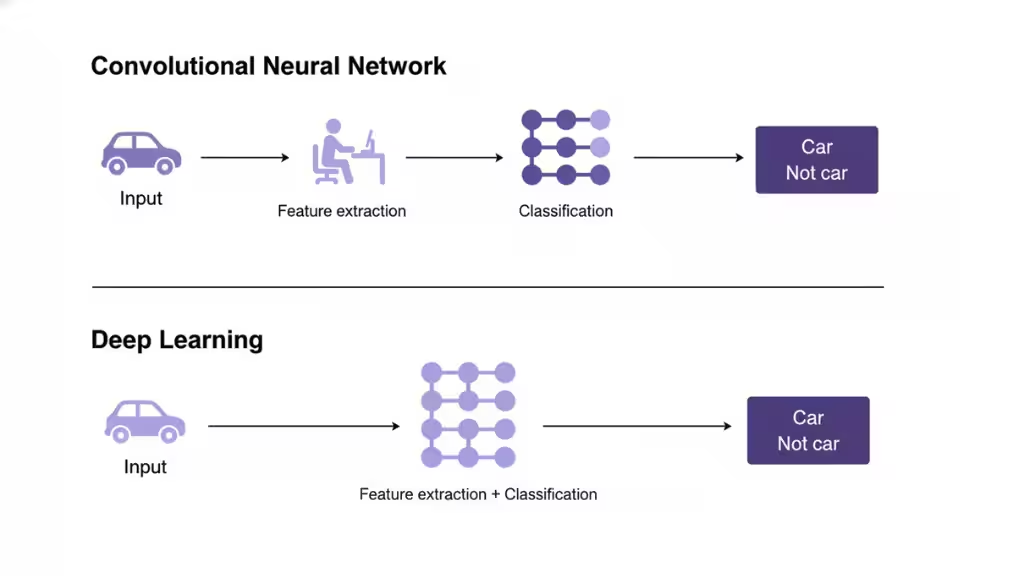

Two key technologies of computer vision are Deep Learning and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). Deep learning enables computers to learn from large datasets without explicit programming, while CNNs are a specific type of deep learning architecture that is especially effective at processing image data by breaking it down into pixels and identifying patterns through mathematical operations.

Deep Learning

- What it is: A subset of machine learning that uses artificial neural networks with multiple layers to learn from data.

- How it works: By being exposed to vast amounts of visual data, the network can autonomously identify patterns and features in images.

- Application: It allows systems to perform tasks like object recognition and image classification by learning to differentiate between visual inputs on their own.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

- What it is: A specialized type of neural network designed specifically for processing grid-like data, such as images.

- How it works: CNNs process images by breaking them into smaller parts (pixels) and applying mathematical operations called “convolutions” to detect features like edges, corners, and textures.

- Application: This process is crucial for analyzing visual data, enabling systems to “learn” from images with increasing accuracy through multiple iterations.

How Does Computer Vision Work?

Computer vision systems follow a structured pipeline that transforms raw visual input into meaningful, actionable information. The exact implementation can vary, but most systems go through the following core stages.

Image Acquisition

The process starts with capturing visual data. Digital sensors such as cameras, scanners, drones or other imaging devices provide still images or continuous video streams in formats like JPEG, PNG or MP4. This raw data forms the input that every subsequent stage depends on.

Preprocessing and Image Enhancement

Once the data is captured, it is standardized and cleaned so the system can work with it reliably. Preprocessing typically includes operations such as resizing, normalization, noise reduction, color space conversion and contrast adjustment. Image enhancement may emphasize important structures and reduce irrelevant variations, ensuring that the downstream models receive consistent, high-quality visual input.

Feature Extraction

After preprocessing, the system converts raw pixels into more informative representations. At this stage, it identifies visual patterns such as edges, textures, shapes and color distributions. In classical approaches, these features are computed with explicit algorithms; in modern systems, deep neural networks learn multi-level features automatically, layer by layer. The result is a compact description of the image that captures the information needed for recognition and decision-making.

Model Training and Analysis

Feature representations are then linked to semantic meaning through machine learning models. During training, the system is exposed to labeled examples so it can learn to associate feature patterns with categories or tasks. Convolutional neural networks, object detection architectures and transformer-based models are common choices, depending on whether the goal is classification, detection, segmentation or a combination of tasks.

At run time, the trained model analyzes incoming features to detect and recognize objects, assign them to predefined classes and infer relationships between them. This is where the system moves from low-level descriptions of “what the image looks like” to structured information about “what is present” and “what it represents.”

Output, Interpretation and Decision-Making

In the final stage, the system produces an output based on its analysis. This might take the form of a label, a set of bounding boxes, a segmentation mask, a text description or a higher-level decision. Internally, this output is also interpreted in context: detected entities are grouped into categories, prioritized and evaluated against rules or downstream logic to decide what should happen next.

In many applications, these outputs feed into larger systems that log results, trigger automated actions or update models over time. Taken together, these stages enable computer vision systems to progress from raw pixels to perception, turning unstructured visual data into structured, meaningful outcomes that other components can understand and act on.

Computer Vision Tasks

Computer vision algorithms can be trained on many different tasks. Each task focuses on a specific way of interpreting visual data, from simple classification to detailed scene understanding and quality inspection. The most common tasks include image classification, object detection, image segmentation, object tracking, face and person recognition, edge detection, image restoration, feature matching, scene understanding, scene reconstruction, optical character recognition, video motion analysis, pose estimation, image generation, and visual inspection.

- Image Classification

- Object Detection

- Image Segmentation

- Object Tracking

- Face and Person Recognition

- Edge Detection

- Edge Detection

- Image Restoration

- Feature Matching

- Scene Understanding

- Scene Reconstruction

- Optical Character Recognition

- Video Motion Analysis

- Pose Estimation

- Image Generation

- Visual Inspection

Image Classification

Image classification assigns one or more labels to an image based on what it contains. Given an input image, the model predicts the most likely class from a predefined set, such as cat, dog, tumor, or no tumor.

Modern systems typically use convolutional neural networks (CNNs) trained on large labeled datasets. During training, the network learns to detect patterns such as shapes, textures, and colors that distinguish one class from another. In production, classification is often the first step in an automated decision pipeline, for example, deciding whether a medical image should be flagged for further review.

Object Detection

Object detection identifies and localizes multiple objects within a single image or frame. It combines two core ideas:

- Object localization, which predicts where objects are by drawing bounding boxes.

- Image classification, which assigns a label to each box (e.g., car, bus, pedestrian).

In traffic footage, for example, an object detection model can detect all vehicles, classify them, and show where they appear in the scene.

Common architectures include R-CNN-style two-stage detectors, which first propose regions of interest and then refine them, and single-stage detectors such as YOLO (You Only Look Once), which perform localization and classification in one pass and are fast enough for real-time use.

Image Segmentation

Image segmentation provides a pixel-level understanding of an image. Instead of just drawing boxes, it divides the image into segments and assigns each pixel to a class or object instance.

Segmentation is more precise than bounding boxes, especially when objects overlap or have irregular shapes. In medical imaging, for example, segmentation can outline tumors or organs with high accuracy, rather than just indicating a rough region.

Segmentation tasks are often grouped into three types: semantic segmentation, where every pixel is labeled with a category (road, building, sky); instance segmentation, where pixels are grouped by individual object instances; and panoptic segmentation, which combines both instance-level separation and full-scene labeling.

Object Tracking

Object tracking follows an object as it moves across a sequence of frames in a video. Once an object is detected, the tracker keeps its identity over time, even as it changes position, scale or orientation.

Tracking is essential in scenarios where motion and behavior matter, such as monitoring a person across surveillance cameras, tracking a ball in a sports broadcast, or following a robot’s target in a factory. Many modern systems combine frame-by-frame detection with motion models to maintain consistent tracks.

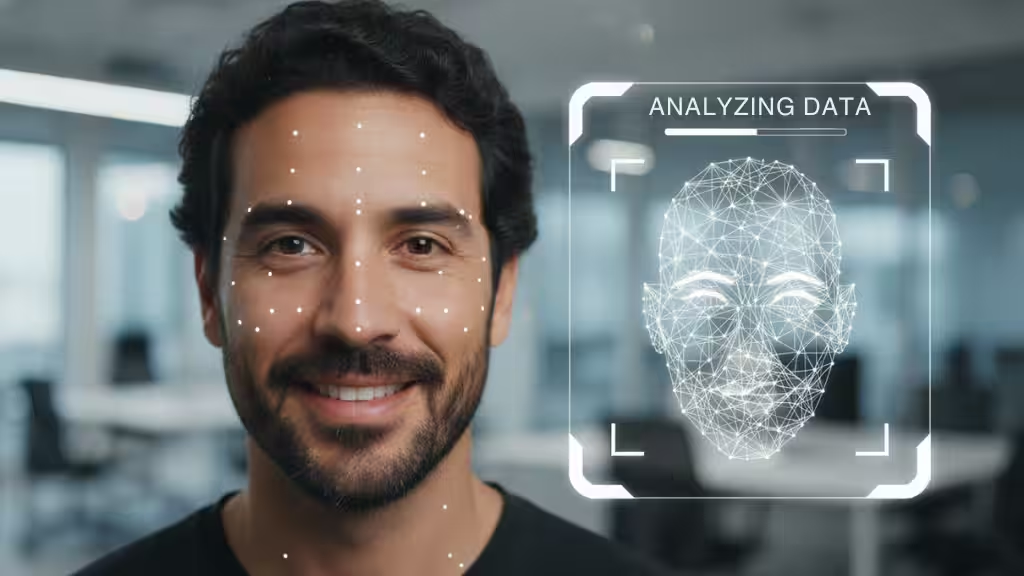

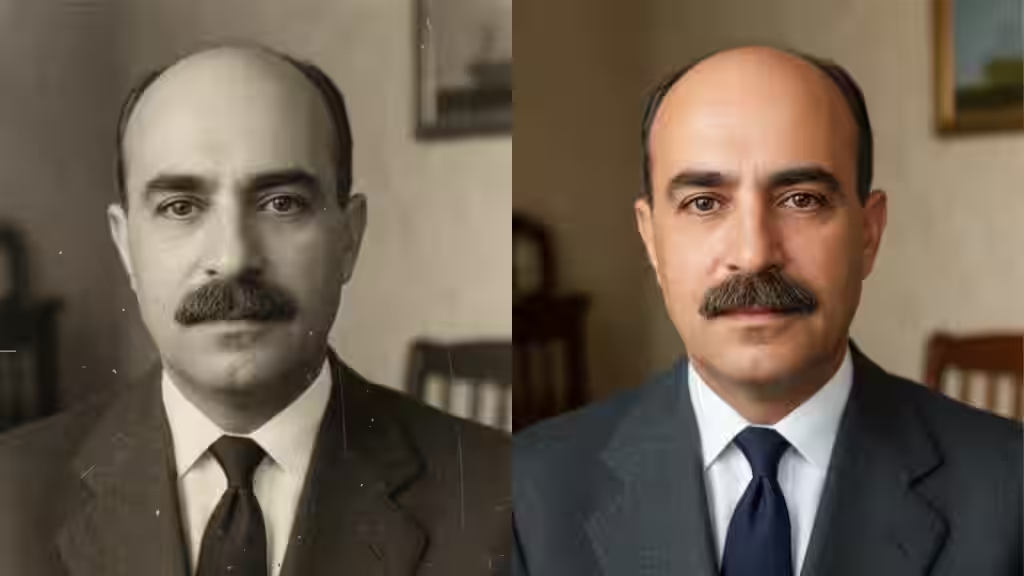

Face and Person Recognition

Face and person recognition focus on identifying who or what a person is, not just detecting their presence. A typical pipeline includes:

- Detecting the face or person in the image.

- Extracting distinctive features, such as distances between facial landmarks or body proportions.

- Comparing these features to stored representations to determine identity or similarity.

This capability underlies biometric authentication (like unlocking smartphones with a face scan), access control systems, and large-scale image search, where users want to find all photos of a particular person in a collection.

Edge Detection

Edge detection finds sharp changes in intensity or color that usually correspond to object boundaries, lines, and contours. Algorithms such as Sobel or Canny filters highlight these transitions and produce an edge map of the scene.

Edge information is often a first step in more advanced tasks. It simplifies the image, making it easier to detect shapes, extract features, or separate foreground from background.

Image Restoration

Image restoration aims to recover a clean, high-quality image from a degraded version. Degradation may be caused by noise, blur, compression artifacts, low resolution or poor lighting conditions.

Traditional approaches use mathematical models and filters, while modern methods rely heavily on deep learning, such as denoising autoencoders or super-resolution networks. Restoration is critical in fields like surveillance, astronomy, historical archiving, and medical imaging, where data quality cannot be easily improved at capture time.

Feature Matching

Feature matching identifies corresponding points or regions between two or more images. The system first detects local features (for example, corners or distinctive textures) and computes descriptors for them, then finds matches across images based on similarity.

This task is foundational for many higher-level applications, including panorama stitching, 3D reconstruction, visual localization, and augmented reality. By knowing how images relate to each other, systems can align them, estimate camera motion or overlay virtual content consistently.

Scene Understanding

Scene understanding goes beyond detecting individual objects. It aims to interpret the overall context of a scene and the relationships between entities: who is doing what, where, and to whom.

Models combine object detection, segmentation and sometimes depth estimation to build a structured representation of the scene. Techniques such as graph neural networks can model spatial and semantic relationships between objects, while vision-language models can generate natural language descriptions like “a person crossing the street in front of a moving car.”

This richer understanding supports applications such as autonomous driving, robotics, and smart environments, where decisions depend on the full context, not just isolated objects.

Scene Reconstruction

Scene reconstruction builds a three-dimensional representation of an environment from two-dimensional images or video. By analyzing multiple views, estimating depth, and inferring geometry, the system creates a 3D model that captures the shape and layout of the scene.

This is used in robotics (for navigation and manipulation), AR/VR (for realistic virtual environments), architecture, and digital twins. Reconstruction can be dense, generating full surface models, or sparse, focusing on key structures and points.

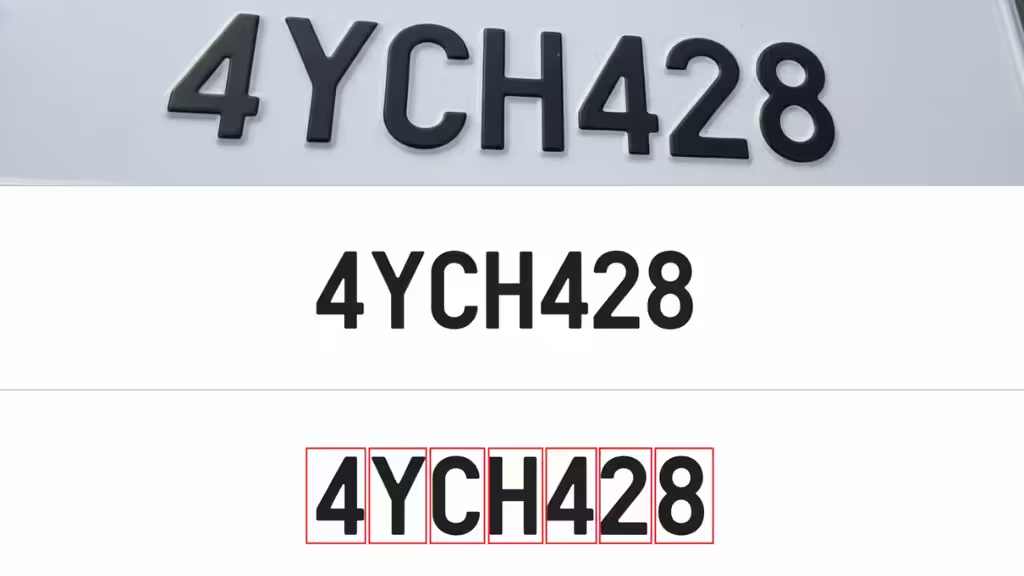

Optical Character Recognition

Optical character recognition (OCR) converts text embedded in images, scanned documents or video frames into machine-readable text.

A typical OCR pipeline includes image capture, preprocessing (such as binarization, noise reduction, and deskewing), and text recognition. The recognition stage locates characters or words and classifies them based on learned patterns.

Modern OCR systems use convolutional and transformer-based architectures to handle different fonts, layouts, and languages. They often work at the word or line level rather than one character at a time, which improves speed and robustness. OCR is central to document digitization, automated form processing, and license plate recognition.

Video Motion Analysis

Video motion analysis focuses on understanding how objects move across time. It may compute optical flow (pixel-level motion), extract trajectories for tracked objects, or detect unusual movement patterns.

This task is used in traffic analysis, crowd monitoring, sports performance analysis, and safety systems. For example, motion analysis can detect sudden runs, falls, or abnormal behavior that may require human attention.

Pose Estimation

Pose estimation estimates the position and orientation of key points on a body or object, typically represented as a skeleton of joints. For humans, this includes shoulders, elbows, knees, hips, and other landmarks.

By tracking these key points, pose estimation enables gesture recognition, activity analysis, and fine-grained motion tracking. It powers applications such as fitness apps that evaluate exercise form, VR systems that mirror a player’s movements, and industrial robots that react to worker positions.

Image Generation

Image generation uses generative models to create synthetic images from scratch, from noise, or from input conditions such as text prompts.

Common model families include diffusion models, which iteratively denoise random inputs to produce realistic images; generative adversarial networks (GANs), which train a generator and discriminator in competition; and variational autoencoders (VAEs), which learn compressed representations of images and sample from that latent space.

Generated images are used for creative content, design exploration, simulation, data augmentation, and more. When combined with language models, these systems can turn natural-language descriptions into detailed visuals.

Visual Inspection

Visual inspection automates the process of checking physical products and structures for defects. Cameras capture images or video of the target, and computer vision models analyze them to spot anomalies such as cracks, scratches, misalignments, or missing components.

Object detection highlights where defects are located, while segmentation can outline their precise shape and size. Visual inspection systems are widely used in manufacturing, electronics, automotive, food processing, and infrastructure maintenance to improve quality, reduce manual labor, and increase safety.

Use Cases of Computer Vision

Computer vision has moved far beyond research labs. It now sits inside products, platforms and workflows across almost every industry. At a high level, most use cases revolve around three core capabilities: understanding scenes (what is happening), identifying entities (who or what is present) and measuring change over time (how things move or evolve). Below are some of the most important domains where computer vision delivers real value.

Healthcare and medical imaging

In healthcare, computer vision helps clinicians interpret complex visual data faster and more consistently. Models trained on medical images can detect signs of disease in X-rays, CT scans, MRIs and pathology slides. A system might classify chest X-rays as healthy or showing pneumonia, segment tumors in MRI scans to estimate their volume, or highlight suspicious regions in mammograms for closer review.

Autonomous vehicles and intelligent transportation

Self-driving cars and advanced driver-assistance systems depend heavily on computer vision. Cameras mounted around the vehicle continually capture the environment. Vision models detect and classify vehicles, pedestrians, cyclists, traffic lights, lane markings and road signs, then track their movement over time.

This visual understanding feeds into planning and control systems that decide when to accelerate, brake or change lanes. Similar techniques power traffic monitoring infrastructure: cameras at intersections can count vehicles, detect congestion, identify accidents and support adaptive traffic light control to improve flow and safety.

Manufacturing and industrial automation

In manufacturing, computer vision is a key enabler of smart factories. Visual inspection systems examine products at each stage of the production line to detect defects such as cracks, missing components, incorrect labels or surface imperfections. Instead of relying on manual inspection, cameras and models provide consistent, high-speed checks and can flag items for rework or rejection.

Robots in industrial settings also use vision for guidance and safety. A robot arm equipped with cameras can locate parts on a conveyor, estimate their pose and adjust its motion to pick or assemble them. Vision-based safety systems can detect when a human worker enters a restricted area and slow or stop machinery to prevent accidents.

Retail, e-commerce and logistics

Retailers use computer vision both in physical stores and online. In brick-and-mortar environments, overhead or shelf-mounted cameras can monitor inventory levels, detect misplaced items and analyze customer movement patterns to optimize store layout. Some cashierless store concepts rely on vision to track which products each customer picks up and automatically generate a bill without requiring a traditional checkout.

In e-commerce, vision models power visual search, allowing customers to upload a photo and find similar products. They also support automated product tagging, content moderation for user-uploaded images and personalization based on what shoppers look at or interact with. In warehouses and logistics centers, computer vision helps track packages, verify labels, measure parcel dimensions and guide mobile robots through complex layouts.

Security, access control, and public safety

Security systems increasingly rely on computer vision to scale beyond what human operators can monitor alone. Cameras at building entrances and secure facilities can perform face and person recognition for access control, ensuring that only authorized individuals enter restricted zones. In larger environments, such as airports or stadiums, vision models can detect suspicious behavior, abandoned objects or unusual crowd dynamics.

Video analytics platforms often combine motion detection, object tracking and event recognition to generate real-time alerts, such as detecting someone entering an off-limits area or crossing a virtual boundary. This reduces the cognitive load on human operators and helps them focus on genuine incidents rather than manually scanning feeds.

Agriculture and environmental monitoring

In agriculture, computer vision supports precision farming by analyzing images captured from drones, satellites or ground-based cameras. Models can identify crop health issues, such as nutrient deficiencies, pest infestations or water stress, often earlier than they become obvious to the human eye. By mapping these conditions across fields, farmers can apply fertilizer, pesticides or irrigation more precisely, reducing waste and improving yield.

Environmental monitoring uses similar techniques at larger scales. Analyzing satellite or aerial imagery, computer vision can track deforestation, urban expansion, droughts, flooding or pollution over time. This helps governments, NGOs and researchers monitor ecosystems, assess the impact of climate events and prioritize conservation efforts.

Sports, fitness and human performance

Sports and fitness applications use computer vision to analyze movement and performance. In professional sports, multiple camera angles and tracking systems follow players and balls, compute trajectories and generate advanced statistics such as speed, distance covered or spatial positioning. Coaches and analysts use these insights to refine tactics and training.

Consumer fitness apps use pose estimation to evaluate exercise form in real time. By measuring joint angles and movement patterns, they can give feedback on posture, depth of squats or correctness of yoga poses. This makes guided training more accessible without specialized hardware.

Augmented reality, virtual reality and human–computer interaction

Augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) depend on computer vision to align digital content with the physical world. AR systems analyze the environment to detect surfaces, track camera motion and recognize known objects or markers. This allows virtual furniture to sit realistically on a floor, game characters to interact with real tables and walls, or instructions to appear exactly over the component being repaired.

In VR and mixed reality, inside-out tracking uses cameras on headsets to reconstruct the surrounding space and track head and controller motion. Vision also enables gesture-based interfaces, where hand and body movements are recognized as input, allowing more natural interaction with digital systems without traditional controllers.

Finance, document processing and identity verification

Financial institutions and enterprises use computer vision to automate document-heavy processes. OCR and document layout analysis can extract structured data from invoices, receipts, forms and contracts, reducing manual data entry and speeding up workflows.

For identity verification, systems combine face recognition with document verification. A user might photograph an ID card and take a selfie; computer vision then checks that the document is authentic, the text matches the account details and the person in the selfie matches the photo on the ID. This is widely used in remote onboarding for banking, fintech and telecommunications.

Infrastructure, inspection and maintenance

Many forms of physical infrastructure bridges, pipelines, railways, wind turbines, power lines require regular inspection. Computer vision enables automated or semi-automated inspection using images captured by drones, robots or fixed cameras. Models can detect corrosion, cracks, deformation, vegetation encroachment or other signs of wear that may require maintenance.

These systems reduce the need for inspectors to work in hazardous conditions, extend the coverage of inspections and allow more frequent monitoring. Over time, historical visual data can be used to predict failure risks and support condition-based maintenance strategies.

Entertainment, media and creative industries

In entertainment and media, computer vision underpins many visual effects and creative tools. Video editing software uses vision to track objects for stabilization or masking, to separate foreground and background, or to apply filters selectively. Motion capture systems track actor movements for animation and games, using pose estimation and tracking to drive digital characters.

Generative models allow artists and designers to explore visual ideas rapidly, generating variations on themes or filling in backgrounds, textures and lighting. Content platforms also use computer vision for recommendation and moderation, automatically classifying and filtering images and video to enforce guidelines and personalize feeds.

Taken together, these use cases illustrate that computer vision is not a single application but a general capability that can be adapted to almost any domain where visual data exists. By combining the core tasks described earlier classification, detection, segmentation, tracking, recognition and generation organizations build tailored solutions that see, understand and act on the world at scale.

Computer Vision Frameworks and Tools

Modern computer vision is powered by a rich ecosystem of libraries and frameworks. These tools handle low-level image operations, high-level deep learning workflows and end-to-end deployment, so you don’t have to reinvent everything for each project. Below are some of the most widely used tools for building computer vision systems.

OpenCV

OpenCV (Open Source Computer Vision Library) is one of the oldest and most popular libraries for computer vision. It focuses on classical image processing and computer vision algorithms and is written in C++ with bindings for Python and other languages.

With OpenCV, you can:

- Load, save and manipulate images and video streams

- Perform operations like filtering, edge detection, thresholding and morphological transforms

- Detect features such as corners and keypoints (e.g., ORB, SIFT-like features)

- Work with geometric transforms, camera calibration and stereo vision

OpenCV is often used for preprocessing, quick prototyping and traditional computer vision pipelines. Even in deep learning systems, it’s common to use OpenCV for data loading, augmentation and visualization while delegating model training to a deep learning framework.

PyTorch

PyTorch is a deep learning framework widely adopted by researchers and practitioners, especially for computer vision and natural language processing. It provides a flexible, Pythonic interface and dynamic computation graphs, which makes experimentation and debugging more intuitive.

For computer vision, PyTorch offers:

- Tensors and GPU acceleration for efficient numeric computation

- High-level APIs to define and train neural networks

- TorchVision, a companion library with common vision datasets, model architectures (like ResNet, Faster R-CNN, Mask R-CNN) and image transforms

PyTorch is heavily used in research because it makes it easy to implement custom architectures and training loops. It is also used in production through libraries like TorchServe, ONNX export and integration with deployment frameworks.

TensorFlow

TensorFlow is another major deep learning framework, widely used in industry. It supports both Python and other languages and provides a scalable runtime for training and deploying models on CPUs, GPUs and TPUs.

For computer vision, TensorFlow provides:

- Keras, a high-level API that simplifies model definition and training

- TensorFlow Vision and example models for classification, detection and segmentation

- Tools for serving models in production, including TensorFlow Serving, TensorFlow Lite (for mobile and embedded) and TensorFlow.js (for running models in the browser)

TensorFlow is often chosen for larger, production-grade systems where tooling around deployment, model management and cross-platform support is important. Many pre-trained computer vision models are available in TensorFlow format through model zoos and hubs.

YOLO (You Only Look Once)

YOLO is a family of object detection architectures designed for real-time performance. Unlike two-stage detectors that first propose regions and then classify them, YOLO performs detection in a single pass, directly predicting bounding boxes and class scores from the input image.

Key characteristics of YOLO-based models:

- End-to-end detection in one forward pass

- Good trade-off between speed and accuracy, suitable for live video and embedded devices

- Implementations available in frameworks like PyTorch, and often wrapped in easy-to-use repositories and tools

Developers use YOLO when they need fast, reasonably accurate object detection for tasks such as traffic monitoring, people counting, retail analytics or robotics. Variants and forks of YOLO provide options tuned for speed, accuracy or specific deployment targets.

scikit-image

scikit-image is a Python library for image processing built on top of NumPy and SciPy. It focuses on clear, well-documented implementations of classical algorithms rather than deep learning.

With scikit-image, you can:

- Perform common image processing routines (filtering, denoising, morphology)

- Work with segmentation, feature extraction, and color space conversions

- Analyze measurements from labeled regions, such as area, perimeter or intensity

scikit-image fits well in scientific and analytical workflows, especially in combination with libraries like pandas, matplotlib and scikit-learn. It is often used when you need interpretable, algorithmic processing rather than training deep models, or as a lightweight alternative to OpenCV in pure Python environments.

Together, these tools cover most of the computer vision lifecycle: OpenCV and scikit-image for classical processing, PyTorch and TensorFlow for deep learning, and YOLO as a specialized solution for high-performance object detection. A typical project will mix several of them for example, using OpenCV for video capture and preprocessing, PyTorch or TensorFlow for model training, and a YOLO-based model for fast detection in production.

A Brief History of Computer Vision

Computer vision might feel like a very modern field, but its roots go back more than half a century. The story of computer vision is really the story of three converging trends: better algorithms, more data, and more compute.

| Years / Period | Description |

|---|---|

| 1950s–1960s | Early work on pattern recognition and artificial neurons. Systems like the Mark I Perceptron showed that simple image classification (e.g., distinguishing basic shapes) was possible, marking some of the first practical “seeing” machines. Computer vision began to emerge as a distinct research area, focusing on edges, simple 3D reconstruction, and basic pattern recognition. |

| 1970s–1980s | Development of core image processing and feature extraction techniques. Researchers built algorithms for filtering, edge detection, and simple feature detectors, enabling more robust analysis of real-world images. Early end-to-end pipelines appeared in robotics and industrial inspection, combining image capture, preprocessing, and rule-based decision logic. |

| 1990s–2000s | Shift toward statistical learning with engineered features. Computer vision systems relied on hand-crafted descriptors (edges, corners, textures, SIFT-like features) combined with machine learning models such as SVMs and boosted trees. CNNs were known but not yet practical at scale, so “classical vision” (features + shallow models) dominated applications like face detection and document analysis. |

| 2010s | Deep learning revolutionized computer vision. Large labeled datasets, GPUs and improved training methods enabled deep CNNs to outperform classical approaches by a large margin. Models like AlexNet, VGG, Inception, and ResNet set new benchmarks in image classification and were quickly adapted for object detection, segmentation, pose estimation, and more, pushing performance to near or above human level on several benchmarks. |

| 2020s–present | Rise of transformers, foundation models, and multimodal vision. Vision Transformers (ViT) became strong alternatives to CNNs for many tasks. Large multimodal models jointly process images and text, enabling capabilities like image captioning, visual question answering and text-to-image generation. Computer vision is now tightly integrated with broader AI systems and used as a core component in many real-world products and services. |

Future Trends of Computer Vision

Computer vision is moving from “models for single tasks” to general visual intelligence that works across tasks, modalities and devices. Below are the key trends shaping where the field is heading over the next few years, especially for developers and researchers.

Foundation models and task-agnostic vision

Traditionally, you trained a separate model for each task: one for classification, another for detection, another for OCR, etc. The current trend is toward foundation models for vision: very large models pretrained on massive, diverse datasets that can be adapted to many downstream tasks with minimal fine-tuning.

These visual foundation models (VFMs) act as general feature extractors or even full “all-purpose” vision systems. Instead of starting from scratch, you load a pretrained vision backbone (CNN or ViT), freeze most layers and fine-tune on your specific dataset. This dramatically reduces data and compute requirements, and it aligns with the broader move toward task-agnostic architectures that can support detection, segmentation, retrieval and more from the same base model.

Multimodal and vision-language models

Computer vision is no longer just about pixels. A major trend is multimodal models that combine vision with language, audio, sensor data and even robot actions. Vision-language models (VLMs) and large multimodal models (MLLMs) can look at an image and:

- Describe it in natural language

- Answer questions about it

- Follow instructions like “highlight all damaged parts and explain why”

Research and industry reports show rapid growth in these multimodal systems, with 2025 seeing a big shift toward models that can reason over images and text together, follow instructions and reduce hallucinations.

In practice, this means future computer vision applications will look more like conversational tools: instead of just returning bounding boxes, they’ll provide explanations, summaries and step-by-step reasoning grounded in visual inputs.

Self-supervised and weakly supervised learning

Labeling large image datasets is expensive and slow. A strong trend is toward self-supervised learning (SSL) and other weakly supervised methods that learn from unlabeled or lightly labeled data. In self-supervised setups, models create their own training signals by solving pretext tasks (like predicting masked patches or augmentations) and then reuse those representations for downstream tasks.

Recent work shows SSL-trained vision models can approach or surpass performance of fully supervised models in many domains, especially where unlabeled data is abundant (medical imaging, satellite imagery, industrial video). For practitioners, this means:

- Less dependence on meticulously labeled datasets

- Easier transfer to new domains with very few labels

- Stronger, more general embeddings for retrieval and anomaly detection

Edge AI vision and on-device intelligence

Another clear direction is pushing vision models out to the edge onto cameras, phones, AR glasses, robots and embedded devices rather than sending everything back to the cloud. Edge AI vision brings:

- Lower latency (critical for robotics, vehicles, safety systems)

- Better privacy (raw video never leaves the device)

- Reduced bandwidth and cloud costs

Reports on edge AI vision highlight key trends like smaller, quantized models, hardware accelerators, and pipelines optimized for real-time inference in constrained environments.

For developers, this means focusing more on model efficiency (pruning, distillation, quantization) and hardware-aware design, not just raw accuracy.

Generative vision and synthetic data

Generative AI is reshaping computer vision from two angles:

- Image and video generation as a capability (e.g., text-to-image, text-to-video)

- Synthetic data for training classic vision models

Diffusion models, GANs and VAEs can now generate highly realistic images and scenes. Beyond creative use cases, this is increasingly used to augment or replace real training data for rare edge cases, privacy-sensitive scenarios (like faces) or dangerous situations (e.g., accidents, defects, hazards).

As tools to generate labeled synthetic scenes improve, you can expect more pipelines where:

- Synthetic images cover rare but critical conditions

- Real data is used mainly for validation and fine-tuning

- Synthetic + real mixtures give better robustness than real-only datasets

3D vision, NeRF-style models and embodied AI

Future computer vision will be much more 3D-aware. Techniques like neural radiance fields (NeRFs) and advanced 3D reconstruction allow models to learn continuous 3D representations of scenes from sparse views, improving AR/VR realism, robotics navigation and digital twins. Many 2026/2027 outlooks for edge vision explicitly call out 3D vision as a key growth area.

At the same time, vision is being tightly integrated into embodied AI robots and agents that see, reason and act. New robotics models combine language, vision and control so that robots can follow instructions like “pick up the blue cup on the left shelf and put it next to the sink,” grounding language in visual perception and physical action.

Domain-specific multimodal vision models

Alongside general-purpose foundation models, we’re seeing the rise of domain-specific multimodal models for areas like healthcare, agriculture and remote sensing. For example, recent work in medical AI trains multimodal vision transformers jointly on multiple imaging modalities (like OCT and SLO scans) plus automatically generated labels, creating powerful retinal foundation models.

These models are tailored to a domain’s particular data types and constraints, giving better performance and reliability than purely general models especially in regulated, high-stakes fields like medicine.

Efficiency, compression and greener computer vision

As models grow, so does the pressure to make them smaller, faster and more energy-efficient. Research from major conferences shows a strong focus on:

- Model compression (pruning, quantization, low-rank factorization)

- Efficient architectures (lightweight ViTs, hybrid CNN–transformer designs)

- Smarter training strategies that reduce compute and memory cost

For practitioners, this means future “best practices” will emphasize accuracy per watt and latency under constraints, not just leaderboard scores.

Responsible, safe and explainable computer vision

As vision is baked into surveillance, healthcare, vehicles and public infrastructure, responsible AI is becoming a first-class concern. Current and forecasted trends emphasize:

- Reducing bias in face and person recognition

- Improving transparency around how decisions are made

- Adding safeguards for safety-critical scenarios (e.g., robotics, autonomous driving)

- Clearer governance around data privacy and surveillance use cases

This is already influencing product and research roadmaps. Expect more tools for auditing models, monitoring for drift and harm, and building vision systems that are not only accurate but also explainable and compliant.

Conclusion

Computer vision has evolved from simple pattern recognition experiments into a mature field that underpins many of today’s most advanced AI systems. At its core, it gives machines the ability to see: to capture visual data, process it, understand it and act on it. That capability now powers applications from medical imaging and autonomous vehicles to retail analytics, robotics, manufacturing and creative tools.

Looking ahead, computer vision will be even more tightly integrated with language, robotics and reasoning. For anyone working in AI today, understanding computer vision is not optional; it’s a core skill that will continue to open doors to new ideas, products and research directions.

FAQs

What is computer vision in simple terms?

Computer vision is a field of AI that teaches computers to understand and interpret visual information from images and videos. Instead of just storing or displaying pictures, computer vision systems analyze them to answer questions like “What is in this image?”, “Where are the objects?” and “What is happening here?”

How is computer vision different from image processing?

Image processing focuses on transforming images enhancing contrast, removing noise, resizing or filtering. Computer vision goes a step further and tries to understand the content of the image. In other words, image processing changes how an image looks; computer vision tries to reason about what the image means.

Is computer vision the same as AI or machine learning?

Computer vision is a subfield of artificial intelligence, and most modern systems rely heavily on machine learning and deep learning. AI is the broader concept of machines performing intelligent tasks, machine learning is the set of techniques used to learn from data, and computer vision is about applying these ideas to visual data specifically.

What are the most common computer vision tasks?

Some of the most common tasks include image classification (assigning labels to images), object detection (finding and labeling objects in images), image segmentation (pixel-level labeling), object tracking (following objects in video), face and person recognition, OCR (reading text in images), pose estimation, image generation and automated visual inspection.

Which programming language should I use to start with computer vision?

Python is the most popular choice for modern computer vision because it has strong ecosystem support: OpenCV, scikit-image, PyTorch, TensorFlow, many pre-trained models and a large community. C++ is also common in performance-critical or embedded applications, often in combination with Python for prototyping.

Do I need a deep learning background to work with computer vision?

You can start without a deep learning background by using classical techniques and pre-built models from libraries. However, for modern, high-performance systems, understanding the basics of deep learning (neural networks, convolution, training, overfitting, and evaluation) is increasingly important. A practical approach is to start with ready-made models, then learn the underlying concepts as you customize and fine-tune.

What kind of data do I need to train a computer vision model?

You typically need a large set of images (or video frames) that are representative of the problem you want to solve, along with labels. For classification, labels might be categories; for detection, bounding boxes; for segmentation, pixel-level masks. Newer approaches like self-supervised learning and synthetic data can reduce the amount of manual labeling required, but having clean, relevant data is still crucial.

Where is computer vision used in everyday life?

Even if you don’t see it, computer vision is running behind the scenes in many places: face unlock on phones, automatic tagging in photo apps, product recommendations based on what you look at, traffic cameras, warehouse robots, quality inspection in factories, content moderation on social platforms and document scanning in banking apps.

Is computer vision only for big tech companies?

No. With open-source libraries, cloud APIs and pre-trained models, small teams and even individual developers can build useful vision applications. You can start with simple use cases like automatic document scanning, basic defect detection or small-scale analytics and scale up as your needs and resources grow.

What are the main challenges and risks in computer vision?

Some key challenges include dealing with limited or biased data, handling edge cases and environmental variation (lighting, occlusion, motion blur), ensuring robustness to attacks or adversarial inputs, and meeting latency and resource constraints on edge devices. On the risk side, face and person recognition raise privacy and fairness concerns, and vision errors in safety-critical domains (such as healthcare or autonomous driving) can have serious consequences. Designing, testing and monitoring systems carefully is essential.

This page was last edited on 19 November 2025, at 12:12 pm

Contact Us Now

Contact Us Now

Start a conversation with our team to solve complex challenges and move forward with confidence.